If Arundhati Roy wrote JavaScript

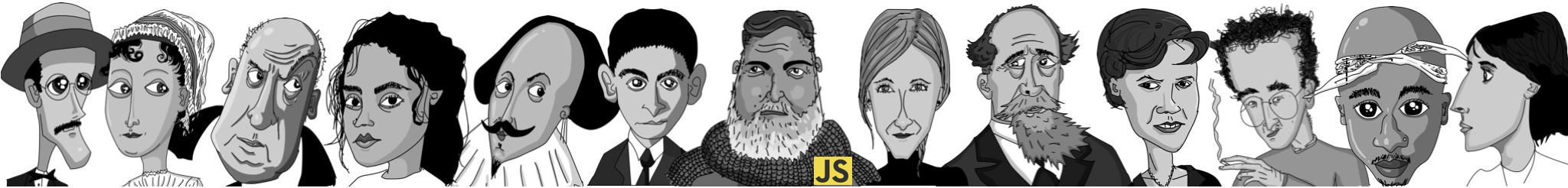

Angus Croll’s If Hemingway Wrote JavaScript is a beautifully illustrated book full of code snippets that are rich in their use of fundamental JavaScript abstractions and modern programming patterns. Born out of equal love for both literature and JavaScript, this book is a whirlwind tour through imaginary GitHub repos belonging to some of the most celebrated wordsmiths of our time, from Shakespeare to JD Salinger to Tupac, including of course Ernest Hemingway.

No Starch Press has been publishing many thoroughly readable programming books over the years, including the much-acclaimed Eloquent JavaScript and Learn You Some Erlang for Great Good! Although If Hemingway has a far more leisurely style than the other books, it is by no means a lesser spectacle of code craftsmanship. Reading some of the examples requires (or, like in my case, inspires) a proper understanding of scoping, hoisting, and closures among other ideas.

The Challenge #

In this post, I’ll introduce a few basic JavaScript abstractions with help from one of Angus’s snippets, taken from the chapter on Arundhati Roy. The challenge is to create a chainable function that takes one string(word) per function call, but when called without an argument, returns a list of all previously passed-in words. e.g., the function sayIt() will be used thus:

console.log(sayIt("Hello")("world!")());

…resulting in the following:

Hello world!

Arundhati Roy’s JavaScript solution #

The plot of The God of Small Things is non-linear. So is Roy’s JavaScript code.

- Angus Croll

Here it is in all its glory, reproduced with permission from Angus and No Starch:

// 1) Start with the answer. 2) Move on to the Grubby Details.

// A viable try-able plan.

function sayIt(word) {

return TheSayItSaveItThing(word);

// Does Whatever-it-is-you-need-it-to.

// Loyal, Dependable, Weak-kneed.

function TheSayItSaveItThing(word) {

// When invoked it Saves.

KochuFunction(word);

// When addressed it Says.

TheSayItSaveItThing.toString = function() {

return TheStretchableFetchableThing.join(' ');

}

// Then it waits to be re-summoned.

// Not invoking. Not recursing. Just waiting.

return TheSayItSaveItThing;

}

// Why change KochuFunction when KochuFunction can change itself?

function KochuFunction(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing = [word];

KochuFunction = function(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing.push(word);

}

// KochuFunction is no longer what it was.

// Or thought it'd be. Ever.

}

}

Roy’s debut JavaScript function, received with almost the same fanfare as her debut novel.

There are more than a couple of things going on here.

Scoping #

For months, JavaScript’s scoping rules remained a source of confusion for me thanks to the C-style syntax and constructs. I finally had my moment of clarity after coming across an excellent blogpost on the subject. One major takeaway from that post is that names in JavaScript have function-level scope as opposed to the C family’s block-level scope. What this means is that in C++ (for example) the if and while blocks have their own scopes, isolated from all external scopes while in JavaScript, scope isolation exists only for functions, not blocks. The following is an illustrated example:

In C++:

int a = 5;

if(1) {

int a = 6;

}

cout << a; // Prints 5

In JavaScript:

var a = 5;

if(true) { // This if-block has no scope of its own, and as a result...

var a = 6; // ...'a' still references the variable declared two lines above

}

console.log(a); // Prints 6

The story of sayIt() revolves around three main characters. The functions TheSayItSaveItThing() and KochuFunction(), and the list TheStretchableFetchableThing. Let’s take a closer look and identify the scope of each.

sayIt() works by maintaining an ordered list of all the passed-in arguments. This list, TheStretchableFetchableThing is never formally declared as a var. The interpreter will therefore assign it to the topmost(global) scope.

TheSayItSaveItThing() and KochuFunction() on the other hand are declared as functions inside sayIt(), and are therefore assigned to sayIt()‘s function-level scope.

Hoisting #

The outermost function, sayIt() has a return statement sitting neatly on top of all other lines of code. Hoisting is the process by which JavaScript pulls all var and function declarations to the top of their respective scopes. Hoisting is what is responsible for ensuring that TheSayItSaveItThing() and KochuFunction() are defined before that return statement is executed.

As opposed to how we see the code, here is how the interpreter sees it:

function sayIt(word) {

// KochuFunction()'s definition has been hoisted

function KochuFunction(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing = [word];

KochuFunction = function(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing.push(word);

}

}

// TheSayItSaveItThing()'s definition has also been hoisted

function TheSayItSaveItThing(word) {

KochuFunction(word);

TheSayItSaveItThing.toString = function() {

return TheStretchableFetchableThing.join(' ');

}

return TheSayItSaveItThing;

}

return TheSayItSaveItThing(word);

}

Closures #

In JavaScript, a closure is created when a function accesses a name that was declared in an external scope. Or in other words, a closure is an inner function accessing variables that were declared outside its own function-level scope.

In the program above, for example, both TheSayItSaveItThing() and KochuFunction() are closures, accessing the global TheStretchableFetchableThing. Additionally, TheSayItSaveItThing() also accesses KochuFunction(). Closures are a very powerful JavaScript feature, as best explained here.

'The Russian Doll’ #

The power of scoping, hoisting and closures is revealed in the definition and subsequent re-definition of KochuFunction() in the code above. The first call to KochuFunction() seeds a new list with the passed-in argument, and then changes its own definition, so that subsequent calls will simply keep pushing to this list.

Angus Croll calls this the Russian Doll pattern. Peter Michaux calls this the lazy function definition pattern.

Often I’ve found myself writing functions that must do something one way the first time, and then a different way the next time. My own inelegant solution has always looked something like this:

int firstCall = true;

if(firstCall) {

// do something

firstCall = false;

} else {

// do something else

}

However, with this approach, each function call has an associated branching cost. The if statement needs to be checked for all the calls, even though the result will be the same every time except the first. The Russian Doll pattern eliminates this unnecessary cost by changing the function’s definition after the first invocation!

// KochuFunction()'s definition has been hoisted

function KochuFunction(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing = [word];

// KochuFunction redefines itself inside its own body, like a Matryoshka doll

KochuFunction = function(word) {

TheStretchableFetchableThing.push(word);

}

}

If Hemingway wrote JavaScript has been a fascinating read so far, and I highly recommend it to admirers of JavaScript everywhere, the same way I’d recommend The God of Small Things to admirers of English literature.